The Regina Tram: The Fall of Regina’s Public Transport

In the fall term of 2023, The REM partnered with the University of Regina’s Urban Geography class 246. The REM came into the classroom to teach the students the benefits of using source documents in the form of archives and interviews for research. Here is the fifth student report, “The Regina Tram: The Fall of Regina’s Public Transport” by Ethan McAlpin and John Mackie.

In 1911, Regina introduced the Municipal Railway on July 28 to haul people and products (Hope To Try, 1911). For a city that inhabited about 30,000 people and expected visitors in large numbers, the inaugural day promoted the transport system, stapling Regina as a city that moved with progress (Hatcher, 1971). As the city grew, more people used the service to shop or work, peaking at about 3000 citizens every half an hour on two streets alone (Municipal Railway Aids, 1958). Even in winter, citizens were hardly concerned with snow since the electric-powered streetcars could clear tracks, taking away the need for machinery or citizens to clear a path (see Figure 1). Despite the streetcar's popularity, the city grew, encouraging citizens to use other forms of transportation, leading to the decline of the streetcar. A catalyst to the decline was the car barn fire, making the dismissal of the streetcar inevitable. In reflection of the streetcar’s usage and history, the city saw personal vehicles and coach buses as the future of their sprawling city, letting the fire become the final arbiter in removing the streetcar system.

The Beginning

Figure 1. Motormen standing on Snow Plow Streetcar, From Regina Municipal Railway Snow Plow. (1931). General Photos (CORA-A-164), City of Regina Archives, Regina, Canada. https://memorysask.ca/regina-municipal-railway-snow-plough. Public Domain.

Regina’s streetcars had multiple functions like efficient passenger travel and product shipment, but the streetcar began as a competition against Moose Jaw (Hatcher, 1971). This competition was good for Regina because Regina would be more desirable for industry. After all, the railways could be used for the transportation of goods like coal, gravel or garbage, which can help grow industry in Regina (Hatcher, 1971). Although the council thought the streetcar would be profitable to the city through industry, it was primarily used for citizens, so it not be as profitable with the low density. The council was warned that the streetcar would not be profitable due to low population density, but the council and many newspapers continued to advocate for the streetcar (Regina’s Municipal, 1910). Continuing with the streetcar system, the council arranged for a municipally-owned railway (Hatcher, 1971). This meant that the council had to limit the system by stopping at the city borders (North Battleford, 1912). However, a government-run system allowed profit and scheduling could be controlled by the public. Despite these limitations, citizens rejoiced with free fare as the Tram travelled across Regina streets—such as Scarth and Eleventh—on the inaugural day, July 28, 1911 (Hope To Try, 1911). Although the system was attractive to the residents, the system brought massive debts to the city from day one because of the rapid expansion of the system. However, the implementation of this system meant quick and affordable travel across Regina. The system created jobs—an idolized one at that—with sufficient pay but caused many years of deficits (Seiberling, 1980). As the city grew, the deficit increased to accommodate the need for more tracks. In 1945, the deficit decreased to $986,000 and with the rise of personal vehicles, the revival of the streetcar was prevented (Oberfeld, 1971). The city’s deficit deficit continued and clients left for new transportation despite the city's move to gasoline buses.

Gasoline Powered

Figure 2. Citizens Clearing Railway Path. From Clearing Snow From Tracks. [ca. 1910s]. General Photos (CORA-A-155), City of Regina Archives, Regina, Canada. https://memorysask.ca/clearing-snow-from-tracks. Public Domain.

For consumers and shipments of heavy equipment, the rail system was excellent for businesses and consumers alike, but that was until gasoline vehicles became more prevalent among the populace. In the 1930s, Regina began using gas-powered buses to improve travel (Argan et al., 2002). Despite the atmospheric impact (something that was not of concern in the early 20th century), gasoline vehicles gave individuals more freedom to choose when and where they travelled. Understanding the issue, developers wanted more tracks in underdeveloped areas, which created more problems for the streetcar (Hatcher, 1971). By laying tracks too quickly, the streetcar lost the purpose of affordability and proximal travel. Although the streetcar had 30 streetcars at its height, it was not enough to meet the growing city's needs (Hatcher, 1971 ). A central issue was laying and cleaning the track, which caused concerns about the timeliness of the service. Another issue was streetcars colliding with snowdrifts (Seiberling, 1980). These snow drifts would cause delays because not all cars had plows. This caused delays in the otherwise predictable system, and citizens would have to wait for the path to be cleared by them or motormen (see Figure 2). As well, the streetcars were also not entirely safe. Passengers and drivers would be exposed to the environment, and there were cracks in the floor that you could see through (Seiberling, 1980). Citizens noticed the opposite with cars. The car could go off track, avoid barriers, keep passengers from the cold, and be available whenever, on the consumer’s time, not the cities. The car’s association with freedom played well into the liberal narrative of individual freedom, which was being prioritized leading into the early years of World War II and after that. Although the car would align with the new norm of low proximity and convenience, citizens would have to become used to the city’s transport system due to the depression and the rationing of gasoline and rubber (Argan et al., 2002). Thus, streetcars were used instead of cars because they used electricity and metal tracks, expressing to citizens the sustainability of streetcars. After the war, citizens returned to their ambitions of coach buses and personal vehicles, eventually leading to personal vehicles taking over. In 1954, cars took nearly half a million clients each year from public transport despite coach buses being a better service than streetcars (Municipal Railway Aids, 1958). The limitations of government public transport rang true for Regina council as many may regret the choice of a municipal streetcar which is limited to city borders unlike private systems (North Battleford, 1912). It was evident that streetcars were no longer relevant. Citizens wanted to travel in comfort, and the streetcar and buses could not provide this, so the city had to be redesigned around personal vehicles, leading to large parking lots and city sprawl.

City Sprawl

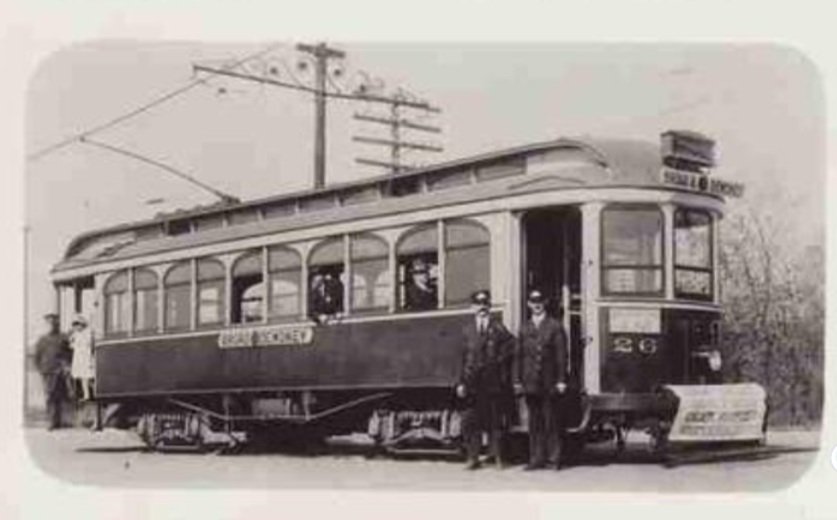

Figure 3. Motormen Standing infron ot Streetcar #26. From Harris, George. (1918). Regina Streetcar #26. General Photos (CORA-A-148), City of Regina Archives, Regina, Canada. https://memorysask.ca/regina-streetcar-26. Public Domain.

As new building philosophies and city designs emerged, Western cities boasted lower-density designs, leading to the strain and downfall of the streetcar for Regina. Before the increased sprawl, the streetcar could make considerable earnings when density was high, clearly shown by Exhibition weekends covering monthly costs in a weekend (Shows Surplus, 1921). For residences, the streetcar soon became irrelevant as some people viewed public transit as inefficient because of the city's new development (Seiberling, 1980). Even before extensive car use, the streetcar would lose revenue from operating in low-density areas that did not provide enough passengers (see Figure 3). So, as low-density sprawl became a prevalent building style, the streetcar was strained, but citizens were happy being away from the increasing congestion, crime, and noise in the core (Resnik, 2010). Since citizens wanted these homes with large yards that were romanticized by the media, developers kept building further from the core, resulting in a cyclical impact of city sprawl and car ownership (Resnik, 2010). This spiral of citizens buying cars for further homes was detrimental to the streetcar. Problematically, the streetcar could not always reach citizens’ homes, especially at the high rate of construction. In 1932, this resulted in the city's plan to remove the street car because urban sprawl made it difficult for Regina to justify investing in it (Municipal Railway Aids, 1958). As the cyclical nature of urban sprawl continued, proximity was no longer a concern as arable land continued to be built upon. The single-family homes with larger yards were encouraged for a long time since they brought money for developers and more taxes to the city. The spreading of citizens strained the system in terms of time and energy costs, making it less effective compared to dense cities. The Regina city transit—despite being similar to successful systems abroad—ran large deficits for 48 years of its life (Oberfeld, 1971). Deficits would continue to increase as the city grew due to factors proximity, construction, and limitations of borders, but the city would soon stumble upon a tragic event that helped transform the system.

The Barn Fire

Figure 4. Aftermath of Streetcar Barn Fire. From Car Barns After the Fire. (1949, January). General Photos (CORA-A-237), City of Regina Archives, Regina, Canada. https://memorysask.ca/car-barns-after-the-fire. Public Domain.

The nail in the coffin for the Regina tram and trolley system was a massive and devastating fire on January 23rd, 1949 (Macpherson, 1949). The fire occurred in the morning when very few workers were on shift, resulting in few people initially fighting the fire (Hatcher, 1971). Of the sixty-two-vehicle fleet, a total number of twenty-two had remained (Hatcher, 1971). The fire had destroyed the vast majority of the barn leaving molten metal and shells of streetcars (see Figure 4). This fire caused the transport system to crumble, resulting in the city needing assistance. Buses and vehicles had been offered by private owners, and even military vehicles temporarily filled transit roles (Macpherson, 1949). These temporary additions assisted people in reaching their jobs and accessing shops downtown. However, the use of private vehicles generated a reflection on public transport reliability, contributing to higher vehicle ownership. As people enjoyed these temporary services, some portions of the public transport were still intact, allowing maintenance bays to service remaining vehicles (12 New Trolleys, 1949). Subsequently, these bays allowed the system to stay in place for the next year, but the streetcar system would not be strong enough to maintain order, and the cost of replacement and insurance would coordinate with the city's plans to remove the streetcar as per their 1932 policy (Municipal Railway Aids, 1958). Coincidently, the fire occurred around the same time that other cities like Saskatoon were removing their tram systems in favour of trolleybuses, so the costs to replace the streetcars were instead used to transform the system (Saskatoon Transit, n.d.). The City of Regina ordered twelve new trolleybuses rather than streetcars to make up for the losses (12 New Trolleys, 1949). The city council could validate this transformation because the insurance company had determined it the city would receive $700,000 in insurance (Macpherson, 1949). The insurance coverage could then cover the $188,500 for ten new gas-powered buses (Oberfeld, 1971). As Regina used the coach buses more, it was finally decided to have the streetcar’s final run on September 11th, 1950 (Last Tram Trip, 1950). Although people enjoyed the streetcar, cars and city sprawl initiated the phasing out of the system, but it was not until the catalytic fire completed the symbolic demise of the Municipal Railway system, renaming it the Regina Municipal Transit (Street Railway Thing of Past, 1950).

Conclusion

Although the streetcar system was not removed until after the fire, it was evident that its usage was declining because of gasoline vehicles. The insurance coverage from the fire helped change the transport system to something better for the public, but as time progressed, only personal vehicles would quench the public’s thirst for reliable and unrestricted transport. Paired with continuous outward growth, the streetcar became unjustifiable as the poor zoning laws created entire neighbourhoods that were car-dependent. This resulted in citizens following the automobile trend that permeated most Western cities, incorporating Regina into the hivemind mentality that converted to gas-powered buses for progress. This advancement and sprawl resulted in the streetcar's increasing deficit, causing the city council to no longer see the benefits of the streetcar. Although the transport system has disappeared, the streetcar is a memory of sacrifice for progress that was once a historical contributor to passenger and industrial transport in Regina.

References

Argan, W. P., Cowan, P., Staseson, G. W. (2002). Regina: the First 100 Years: Regina’s Cornerstones: the History of Regina Told Through its Buildings and Monuments (Rev. ed.). Leader-Post Carrier Foundation.

Car Barns After the Fire. (1949, January). General Photos (CORA-A-237), City of Regina Archives, Regina, Canada. https://memorysask.ca/car-barns-after-the-fire

Clearing Snow From Tracks. [ca. 1910s]. General Photos (CORA-A-155), City of Regina Archives, Regina, Canada. https://memorysask.ca/clearing-snow-from-tracks

Harris, George. (1918). Regina Streetcar #26. General Photos (CORA-A-148), City of Regina Archives, Regina, Canada. https://memorysask.ca/regina-streetcar-26

Hatcher, C. K. (1971). Saskatchewan's Pioneer Streetcars: The Story of the Regina Municipal Railway. Railfare.

Hope To Try Out Car System Today: Power Unit in Perfect Running Order—Carmen Recieve Their Instructions. (1911, July 27). The Morning Leader, 8. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2177114319

Last Tram Trip. (1950, September 11). The Leader-Post, 22. https://www.proquest.com/hnpleaderpost/docview/2213561655

Macpherson, W. (1949, January 24). Car Barn Fire Inquiry Opens: Makeshift System Success After $1,000,000 Blaze. The Leader-Post, 1. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2213538451

Municipal Railway Aids City: During Growth. (1958, September 23). The Leader-Post, 41. https://www.proquest.com/hnpleaderpost/docview/2217249377

North Battleford Ratepayers to Vote on Street Railway: Special Meeting of Town Council Considered Referring the Granting of a Street Railway Franchise to a Vote of the Ratepaters. (1912, September 21). The Leader, 25. https://www.proquest.com/hnpleaderpost/docview/2177176955

Oberfeld, Harvey. (1971, July 27). Colorful Transit System History Recalled. The Leader-Post, 3. https://www.proquest.com/hnpleaderpost/docview/2217815153

Regina Municipal Railway Snow Plow. (1931). General Photos (CORA-A-164), City of Regina Archives, Regina, Canada. https://memorysask.ca/regina-municipal-railway-snow-plough

Regina’s Municipal Street Railway. (1910, December 10). The Morning Leader, 4. https://www.proquest.com/hnpleaderpost/docview/2212727096

Resnik, D. B. (2010). Urban Sprawl, Smart Growth, and Deliberative Democracy. American Journal of Public Health, 100(10), 1852–1856. https://doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2009.182501

Saskatoon Transit. (n.d.) History. City of Saskatoon. Retrieved December 5, 2023, from https://transit.saskatoon.ca/about-us/history

Seiberling, Irene. (1980, July 21). Regina Man Remembers When Streetcar Rides Were a Nickel. The Leader-Post, 25. https://www.proquest.com/hnpleaderpost/docview/2218358632

Shows Surplus for First Week in Aug: Street Railway Makes Profit of $3,700 During Exhibition Week. (1921, August 20). The Morning Leader, 13. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2212786680

Street Railway Thing of Past. (1950, September 6). The Leader-Post, 3. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2213527289

12 New Trolleys Ordered. (1949, January 24). The Leader-Post, 1,7. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2213538451